Farewell to Oliver Rackham 1939 – 2015

‘Is it natural or man-made?’

This is the question the voiceover asks at the start of BBC Four’s ‘Unnatural Histories: Amazon‘, first broadcast in June 2011 and repeated last week. The narrator (the writer isn’t credited, so who knows who wrote the script) then says that the future of the Amazon landscape depends on the answer. Well, perhaps it might if we think in dualistic either-or terms, or if we assume that only completely ‘natural’ landscapes are worth protecting. And indeed Survival International has accused some conservationists of excluding all people from designated habitats, as if all human involvement in the land must be harmful, even though they say indigenous people may know how to live there sustainably – so this muddled thinking can still cause harm and suffering.

But the question is meaningless. The answer to ‘Is this landscape natural or man-made?’ is ‘Neither – because it’s both’. And landscapes are made by women as well as men. If the human species were made entirely of males we would have become extinct as soon as we appeared.

All species affect our habitats, some – beavers, for example – more than others. Human beings have lived in just about every part of the planet. Wherever we live, what we do will affect the land, but that’s not a problem in itself – what matters is what we do. We can destroy habitats and species, replace beautiful places with ugly greyness, and pollute the soil and the water and the air with poisons. Or we can choose to live in harmony with our land, protect its rich diversity, and increase the opportunities for wildlife. We may even make it more beautiful, at least to human eyes.

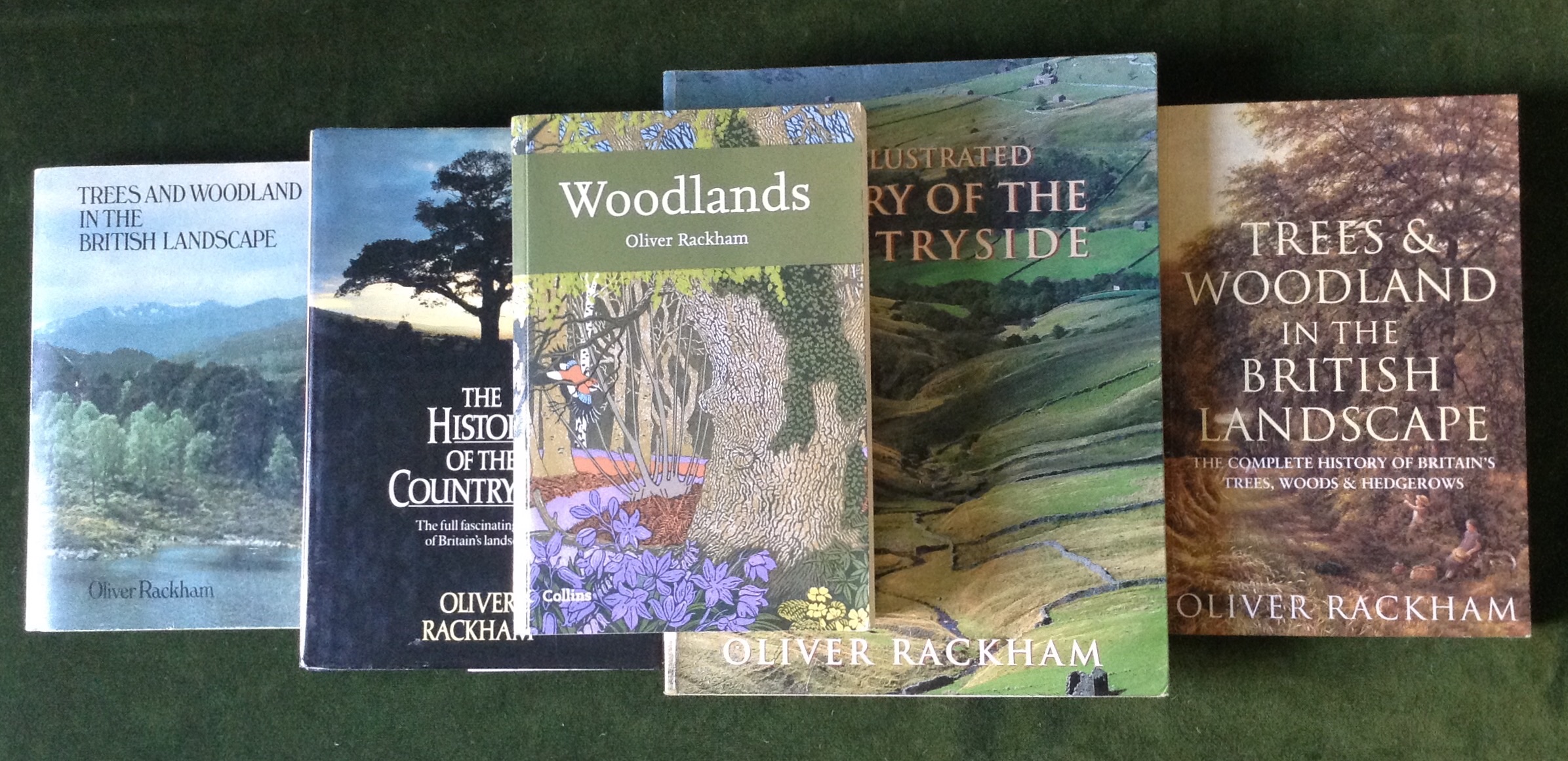

Here in Britain one person who did more than almost anybody else to help us understand our past landscapes, and especially woodland, was Oliver Rackham, who died last week. He studied landscape ecology, and that means studying landscape history. He studied and wrote about both British and Mediterranean landscapes. His books include ‘Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape‘, ‘Ancient Woodland‘, ‘The History of the Countryside‘, and the hundredth Collins New Naturalist, ‘Woodlands‘. They’re all wonderful books, academically rigorous, fully referenced, beautifully illustrated, and very readable. I found ‘Woodlands’ such a good read that I would have read it cover-to-cover in one sitting, given the chance. Only last year his book ‘The Ash Tree‘ was published.

Oliver Rackham knew that the question ‘Is it natural or man-made?’ was meaningless. In the last chapter of the first 1976 edition of his first book, ‘Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape’, he says “The idea that the countryside is somehow ‘natural’ has given way to the equally dubious notion that it is wholly artificial.” His research gave an insight into just how intricate and subtle the relationship between land and people could be. He didn’t foolishly conclude that we could therefore do anything we liked and that all would be well. He always emphasised our need to learn, not to rush into action in blind ignorance. At the end of ‘Woodlands’, published in 2006, he says (about whether before humans arrived Britain was continuously wooded, or whether woods were islands among grassland) that “Conservationists should not yet behave as though they know the answer.”

And he was a powerful advocate for our landscapes and their histories, and the need to defend them against destruction, whether it was malicious and driven by greed, or well-intentioned but thoughtless and ignorant. After saying “The idea that the countryside is somehow ‘natural’ has given way to the equally dubious notion that it is wholly artificial” he continued: “The planting of new groves is thought to be an adequate remedy for failure to conserve existing woods and trees.” Last January, when Owen Paterson, then Secretary of State, suggested it was alright to destroy ancient woods as long as you planted some trees somewhere else (maybe up to fifty miles away), Oliver Rackham spoke out against ‘biodiversity offsetting’.

Climate-friendly gardeners may not have any direct responsiblilty for woods or other important habitats, but we can learn about them, and make sure that what we do in our gardens does not endanger important habitats.

If we can learn not to make simplistic assumptions, if we humans learn honestly from the past and choose wisely for the future, then we can learn to live in harmony with our land, whether that’s the Amazon, or our own countryside here in Britain or just our own small gardens. We can honour Oliver Rackham’s spirit and his work will live on.

Afterword 3 March 2015

I’ve finally made myself watch the rest of ‘Unnatural Histories: Amazon’. Despite my misgivings, it is worth watching, because many of the academics who contribute have something interesting to say, so thank you to the BBC for making and broadcasting it despite the drawbacks.

The famous terra preta, black earth, gets mentioned, but we find out almost nothing about how it’s made. The only indigenous voice we hear outside academia is that of Metua Mehinaku from the Kuikuro tribe, who has a few seconds (at about 43 minutes in) to describe how their ‘organic waste’ (I wonder what the original words were before translation?) is always put at the back of the village, and left for three years, after which it’s planted. That’s it – that’s all we’re told about how it’s produced, though anybody who’s ever heard of it before knows there must be a bit more to it than that. If only we could have had a whole programme on his tribe and what they’re doing in more detail.

I still find the voiceover irritating, not only because there’s no way of knowing who wrote it, or because it’s written in the kind of tabloid journalist style that J. K. Rowling spoofed in ‘The Quibbler‘, but because whoever wrote it still doesn’t seem to understand what we can learn from the academics’ findings: that we don’t have to label things in a simplistic either-or way, and that instead a landscape can be both natural and influenced by people, and that landscapes are not a thing with a single label, but a relationship between different lifeforms, including ourselves. What matters is whether the relationship is a good relationship of mutual interest, or a bad relationship of exploitation and damage.

But by the time we get to the end of the programme any viewer who’s grown out of dualistic immaturity will have understood what some of the first peoples of the Amazon, like many other people around the world (including here in Britain) can teach us: that we humans don’t have to destroy and desecrate, but that we can live in harmony with our fellow creatures, and that we can belong on our land – and that we need to learn from our history, which is how Oliver Rackham chose to live his life.

Climate-friendly gardening

Climate-friendly gardening